Complete Guide to Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Assistants

For many dental assisting students, the term “head and neck anatomy” brings a sense of dread. It conjures images of dense textbooks, impossibly complex diagrams, and a Latin vocabulary that seems designed to be forgotten. If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by this subject, know this: you are not alone. It’s a rite of passage.

But what if you could reframe anatomy? What if, instead of seeing it as a hurdle to overcome, you saw it as your secret weapon?

This guide to Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Assistants is designed to do exactly that. We will strip away the academic intimidation and rebuild your understanding of anatomy from the ground up, focusing exclusively on the practical, clinical knowledge that you will use every single day of your career. This is not just a chapter to pass an exam; this is the operational roadmap that will elevate you from a good dental assistant to an exceptional one.

Mastering this subject is the key to unlocking true clinical confidence. It’s the difference between simply following instructions and anticipating the dentist’s next move. It’s how you become a proactive, indispensable member of the dental team, capable of understanding the “why” behind every procedure, communicating with professional precision, and ensuring the highest level of patient care.

Prepare to embark on a detailed tour of the most intricate and fascinating area of the human body. By the end of this guide, you will have a functional, three-dimensional map of your workspace in your mind, ready to apply on day one.

Part 1: The Foundational Concepts – Building Your Mental Map

This guide will explain head and neck anatomy for dental assistants but Before we can explore the specific structures, we must first learn the language and layout of the land. Approaching anatomy with the right mindset and a basic understanding of its organization is the key to making the information stick

Why Mindset Matters: From Memorization to Application

The single biggest mistake students make is trying to brute-force memorize anatomical terms. This is a recipe for stress and burnout. The goal is not to become a walking dictionary, but a practical navigator. Every time you learn a new structure, your first question should be: “So what? Why does this matter to my job?” When you connect every bone, nerve, and muscle to a real-world clinical task—like taking an X-ray, assisting with an injection, or placing a suction tip—the information suddenly has meaning and purpose. It becomes a tool, not just a fact.

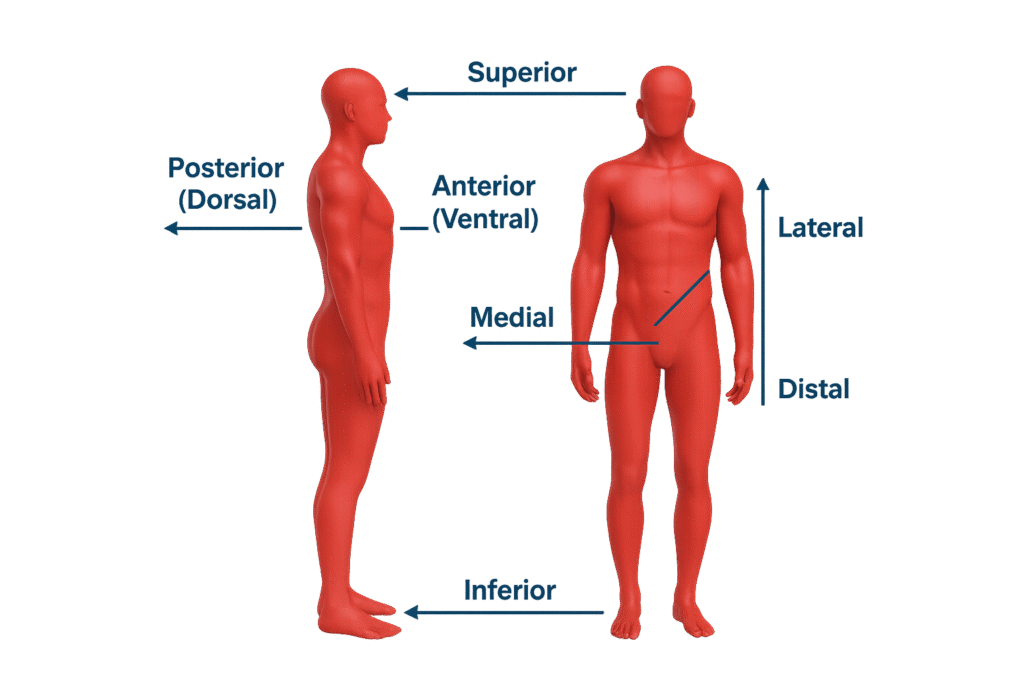

Anatomical Directions & Planes: Your GPS

To describe locations accurately, we use a universal set of directional terms. Think of this as the GPS for the human body.

- Anterior: Toward the front (e.g., the lips are anterior to the teeth).

- Posterior: Toward the back (e.g., the molars are posterior to the canines).

- Superior: Toward the head or above.

- Inferior: Toward the feet or below.

- Medial: Toward the midline of the body.

- Lateral: Away from the midline of the body.

- Proximal: Closer to the trunk or point of origin.

- Distal: Farther from the trunk or point of origin.

- Mesial: (Specific to dentistry) The surface of a tooth that is closer to the midline.

- Distal: (Specific to dentistry) The surface of a tooth that is farther from the midline.

These are viewed within three main planes of section:

Sagittal Plane: A vertical plane that divides the body into left and right portions.

Coronal (or Frontal) Plane: A vertical plane that divides the body into anterior (front) and posterior (back) portions.

Transverse (or Horizontal) Plane: A horizontal plane that divides the body into superior (upper) and inferior (lower) portions.

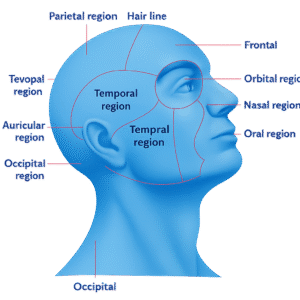

The 11 Regions of the Head: Your Neighborhoods

To simplify the head, we divide it into 11 distinct regions. Knowing these general areas helps orient you.

Frontal (Forehead)

Parietal (Top/sides of head)

Occipital (Back of head)

Temporal (Temples/side, location of TMJ)

Orbital (Eye area)

Nasal (Nose area)

Infraorbital (Below the eye)

Zygomatic (Cheekbone area)

Buccal (Soft cheek area)

Oral (Mouth area)

Mental (Chin area)

Part 2: The Bony Framework: Key Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Assistants”

The skull is the foundational structure upon which everything else is built. It protects the brain and forms the architecture of the face. While it’s composed of 22 bones, your clinical focus will be on two main protagonists.

The Maxilla: The Stationary Anchor

The maxilla is the upper jaw. It’s formed by two bones fused at the midline, making it a strong, stationary unit.

Structure and Function: It holds all 16 upper (maxillary) teeth in bony sockets called alveoli. It also forms the floor of the nasal cavity and the roof of the mouth (the hard palate).

Key Landmarks for a DA:

Maxillary Sinus: These are large, air-filled spaces within the maxilla, located just above the roots of the maxillary premolars and molars.

Maxillary Tuberosity: A rounded bony prominence located just posterior to the last maxillary molar. It’s a key landmark for certain injections and for ensuring full coverage in denture impressions.

Infraorbital Foramen: A small hole located in the infraorbital region, just below the orbit of the eye. The infraorbital nerve and blood vessels pass through here.

Clinical Connection: The bone of the maxilla is relatively thin and porous compared to the lower jaw. This is a critical advantage for anesthesia. It allows the anesthetic solution from a simple infiltration (an injection next to the apex of a single tooth) to easily seep through the bone and numb the targeted tooth. The close proximity of the maxillary sinus means that a severe infection from an upper molar can sometimes spread into the sinus, causing symptoms of sinusitis.

The Mandible: The Dynamic Powerhouse

The mandible, or lower jaw, is the largest and strongest bone of the face. Its most defining feature is that it is the only movable bone of the skull, articulating with the temporal bone at the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ).

Structure and Function: It is a single, U-shaped bone that holds all 16 lower (mandibular) teeth. It consists of a horizontal body and two vertical projections called the rami (singular: ramus).

dmark on the mandible for a dental assistant to know. It is a hole on the inner (medial) surface of the ramus. The inferior alveolar nerve, which provides sensation to all the lower teeth, enters the mandible through this foramen.

Mental Foramen: This is a small hole on the outer (lateral) surface of the mandible, typically located between the apices of the first and second premolars. The mental nerve exits through this foramen to provide sensation to the chin, lower lip, and buccal gingiva in that area.

- Clinical Connection: The mandible’s dense, non-porous bone makes single-tooth infiltrations largely ineffective, especially for molars. To achieve profound anesthesia, the dentist must perform a nerve block. The most common is the Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block (IANB), where the anesthetic is deposited near the mandibular foramen before the nerve enters the bone. This numbs the entire half of the mandible. The mental foramen is the target for a mental nerve block, used for procedures on the lower premolars, canine, and anterior soft tissues.

For a more detailed exploration of these crucial bones, visit our Deep Dive into the Mandible and Maxilla.

Part 3: The Engines of Movement (Myology) The Muscles That Make It Happen

Muscles are the motors that create movement, from the powerful force of chewing to the subtle art of a smile.

The Mighty Muscles of Mastication

This group of four paired muscles is solely responsible for moving the mandible.

Learn more about how these muscles work and their relation to TMD in our Guide to the Muscles of Mastication.

- Temporalis Muscle:

- Location: A large, fan-shaped muscle located on the temporal bone.

- Action: Elevates the mandible (closes the jaw) and retracts it (pulls it backward).

- Clinical Pearl: Patients with tension headaches often experience tenderness in this muscle.

- Masseter Muscle:

- Location: A thick, powerful, rectangular muscle on the outside of the ramus.

- Action: Primarily elevates the mandible (forcefully closes the jaw).

Clinical Pearl: This is the muscle you can easily feel bulge when you clench your teeth firmly. It’s often sore in patients who grind their teeth (bruxism).

Medial Pterygoid Muscle:

Location: Runs on the inner surface of the ramus, like a mirror image of the masseter.

Action: Elevates the mandible (closes the jaw).

Clinical Pearl: Working together with the masseter, it forms a sling that cradles the mandible.

Lateral Pterygoid Muscle:

- Location: Runs horizontally, deep within the cheek area.

- Action: This is the primary muscle responsible for opening the jaw. It also allows for protrusion (pushing the jaw forward) and side-to-side movements.

- Clinical Pearl: Spasms or dysfunction in this muscle are a common cause of TMJ disorders (TMD) and jaw clicking.

- Lateral Pterygoid Muscle:

- Location: Runs horizontally, deep within the cheek area.

- Action: This is the primary muscle responsible for opening the jaw. It also allows for protrusion (pushing the jaw forward) and side-to-side movements.

- Clinical Pearl: Spasms or dysfunction in this muscle are a common cause of TMJ disorders (TMD) and jaw clicking.

The Muscles of Facial Expression

These smaller muscles are responsible for our expressions. From a DA’s perspective, two are critical:

- Orbicularis Oris: The circular muscle that surrounds the lips. It allows you to pucker, close your lips, and is essential for containing food and saliva.

- Buccinator: The primary muscle of the cheek. It presses the cheek against the teeth, which is crucial for keeping food on the occlusal surfaces during chewing and for effective use of straws. For a DA, this muscle is what you are constantly retracting to gain visibility.

Part 4: The Electrical & Plumbing Systems (Neurovasculature) – Nerves, Vessels, and Glands

This is the intricate network that provides sensation, blood supply, and lubrication to the entire region.

The Trigeminal Nerve (CN V): The Undisputed King of Dentistry

If you learn only one nerve, this is it. The Trigeminal Nerve is the fifth cranial nerve and the largest. It is the primary source of sensory information for the face and oral cavity and provides motor function to the muscles of mastication. It has three main branches:

V1 – Ophthalmic Branch

This branch provides sensation to the eyes, forehead, and nose. It is not relevant to dental procedures.

V2 – Maxillary Branch (Purely Sensory)

This branch exits the skull and travels forward to provide sensation to the entire mid-face.

It innervates: All maxillary (upper) teeth, the maxillary sinus, the skin of the cheek and lower eyelid, the upper lip, and the hard and soft palate.

- Key Dental Branches:

- Posterior Superior Alveolar (PSA) Nerve: Numbness for maxillary molars.

- Middle Superior Alveolar (MSA) Nerve: Numbness for maxillary premolars (not present in all people).

- Anterior Superior Alveolar (ASA) Nerve: Numbness for maxillary canines and incisors.

- Infraorbital Nerve: A terminal branch that numbs the cheek and upper lip.

V3 – Mandibular Branch (Sensory and Motor)

This is the largest branch and is unique because it has both sensory and motor fibers. It innervates (Sensory): All mandibular (lower) teeth, the lower lip, the chin, and the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- It controls (Motor): All four muscles of mastication.

- Key Dental Branches:

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve (IAN): This is the main nerve trunk that travels through the mandibular foramen and down the canal within the mandible, providing sensation to all the lower teeth on one side.

- Lingual Nerve: Runs alongside the IAN but on the outside of the bone. It provides sensation to the floor of the mouth and the side of the tongue. This is why the tongue gets numb during a mandibular block.

- Mental Nerve: This is the terminal branch of the IAN that exits through the mental foramen to provide sensation to the chin and lower lip.

Explore our Ultimate Guide to the Trigeminal Nerve (CN V). if this Guide to Head and Neck Anatomy is not enogh.

Glands and Lymphatics

The Major Salivary Glands: These glands produce the saliva that aids in digestion and protects teeth.

Parotid Gland: The largest, located in the cheek, just in front of and below the ear. Its duct (Stensen’s duct) opens into the mouth on the inside of the cheek, opposite the maxillary second molar.

Submandibular Gland: Located in the floor of the mouth, below the mandible.

Sublingual Gland: Located in the floor of the mouth, directly under the tongue.

Clinical Connection: Knowing these locations is key to effective moisture control. Placing the high-volume evacuator (HVE) or saliva ejector near these duct openings is the most efficient way to keep the working field dry.

Part 5: The Workspace – A Detailed Tour of the Oral Cavity

Now, let’s step inside and tour the actual workspace, applying our anatomical knowledge.

- Vestibule: The space between the teeth and the inner surface of the cheeks and lips. This is where cotton rolls are often placed.

- Gingiva (Gums): The soft tissue that surrounds the teeth. The gingival sulcus is the shallow groove between the free gingiva and the tooth, and measuring its depth is a key part of a periodontal exam.

- Hard Palate: The firm, bony front portion of the roof of the mouth. It is covered by specialized masticatory mucosa.

- Soft Palate: The movable posterior third of the palate, ending in the uvula. It rises during swallowing to close off the nasal cavity. Its sensitivity often triggers the gag reflex.

- Tongue: A powerful muscle covered in papillae (which contain the taste buds). It’s essential for speech, swallowing, and cleaning the oral cavity.

- Floor of the Mouth: The area beneath the tongue, where the submandibular and sublingual glands open. It is a highly vascular area.

- Frenum (plural: Frena): A narrow fold of mucous membrane that attaches a more fixed part to a movable part. Key frena include the labial frenum (attaching the lip) and the lingual frenum (attaching the tongue). A short lingual frenum can cause a “tongue-tie” (ankyloglossia).

For a complete exploration of these structures, see our Tour of the Oral Cavity & Its Structures.

Clinical Application of Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Assistants

After reading this guide of head and neck anatomy for dental assistants, you should know that Anatomy is not theoretical. It is the foundation of every single clinical task you perform.

- During Radiography: You align the X-ray beam and sensor based on the long axis of the tooth and surrounding bony landmarks to get a diagnostic image without distortion.

- During Anesthesia: You anticipate which areas will get numb based on the injection site and the nerve being targeted. You can then reassure a patient who is alarmed by their numb tongue after an IANB.

- During Impressions: You select a tray that is large enough to capture all necessary landmarks, from the maxillary tuberosity in the back to the full depth of the vestibule in the front.

- During Extractions: You understand the need to retract the tongue and cheek not just for visibility, but to protect these soft tissues, which are innervated by major nerves, from the instruments being used.

During Coronal Polishing: You adapt your grasp and handpiece angulation to navigate the unique contours and surfaces of each tooth, from the broad buccal surface of a molar to the scooped-out lingual surface of an incisor.

Conclusion: From Student to Confident Clinician

You have just completed a comprehensive journey through the head and neck, from the foundational bones to the intricate networks of nerves. The goal of this ultimate guide was to dismantle the fear surrounding anatomy and rebuild it as your most trusted clinical tool.

Mastering head and neck anatomy for dental assistants is the key to your success. It allows you to understand the “why,” to anticipate, to communicate effectively, and to contribute to your dental team at the highest possible level. This is the bedrock of clinical excellence. Continue to review these concepts, use your own face as a learning tool, and always connect what you’re learning to a real-world task. This is how you transform abstract knowledge into tangible, professional confidence.

Ready to Test Your Knowledge and Solidify Your Learning?

Reading is the first step, but true mastery comes from active recall. Now that you’ve navigated the roadmap, it’s time to prove you know the way.

🧠 Challenge 1: The Ultimate Anatomy Quiz

Do you know your foramen from your fossa? Can you identify the primary muscle that opens the jaw? Take our 25-question interactive quiz designed to test the key concepts in this guide to Head and Neck Anatomy for Dental Assistants. Get instant feedback and see where you shine!

▶️ CLICK HERE TO TAKE THE ULTIMATE ANATOMY QUIZ NOW ◀️

🎮 Challenge 2: The “Anatomy Explorer” Educational Game

Turn learning into a game! In our “Anatomy Explorer,” you’ll race against the clock to drag and drop labels onto the correct anatomical structures. It’s a fun, fast-paced way to reinforce your knowledge and earn your place as an anatomy expert.